Dear Editor,

Readers would recall that this author exposed the Oil and Gas Governance Network (OGGN) for not honouring their legal obligations under U.S tax laws. Shortly after, one of their known members/affiliates, namely Charles Sugrim (accountant/political activist), started a platform of his own to advance what appears to be a partially covert political agenda.

The activist, whom I regard as a supremely qualified finance professional more than myself, and who is also a practitioner in the United States, propagated an egregiously unintelligible speculation in respect of ExxonMobil and the company’s arrangement with its co-venture partners HESS and CNOOC. He posited that when ExxonMobil invited HESS and CNOOC to participate in the Stabroek block as a consortium, that ExxonMobil must have brokered a deal with CNOOC and HESS, alleging that Exxon may have been paid a large sum of money. He even came up with a figure of US$10 billion, which he described as a “reasonable assumption”. Then he contended that, if this is proven to be true, the Government should be paid 50% of that sum, of which 60% should be distributed to every household.

Editor, when someone of Charles Sugrim’s stature makes a “reasonable assumption”, it should not be treated the same way a lay person would make a “reasonable assumption” on the same issue. Mr. Sugrim’s hypothesis can be easily tested and proven or disproven, which I attempt to do hereunder.

First, let’s establish some critical facts before testing Sugrim’s hypothesis. Following the 1999 prospecting licence, ExxonMobil shared a 50/50 partnership with Shell to carry out their exploration activities in the Stabroek block. Owing to a lack of confidence, with no successful find after fifteen years of exploration, Shell exited the partnership with ExxonMobil in 2014. This means that all of the exploration costs that Shell incurred up to the time of its exit were treated as sunk costs. After Shell exited, ExxonMobil were determined to continue with exploration, given their level of confidence. In an OilNow report, Exxon’s country manager revealed that they had written to thirty-five companies, and HESS and CNOOC responded positively. HESS and CNOOC then joined Exxon to form a consortium in 2014. Shortly after, in less than one year, it was announced that crude oil was discovered in commercial quantities in May of 2015.

Now, let’s test the hypothesis. If it is reasonable to assume that ExxonMobil demanded US$10 billion from HESS and CNOOC, an examination of both companies’ financial statements for the years 2014-2015 would prove or disprove this notion. Importantly, let’s understand that US$10 billion is no small and ordinary sum of money. For context, US$10 billion represents 2.5 times Guyana’s pre-oil GDP, and 2.3 times the exploration and development costs for the first field development (Liza 1) in the Stabroek block.

The obvious question that comes to mind is: was it affordable and feasible for HESS and CNOOC at that time to pay ExxonMobil this amount of money just to share the partnership for the Stabroek block? Bearing in mind that HESS and CNOOC would have to share the exploration and development costs together with the associated risks with ExxonMobil.

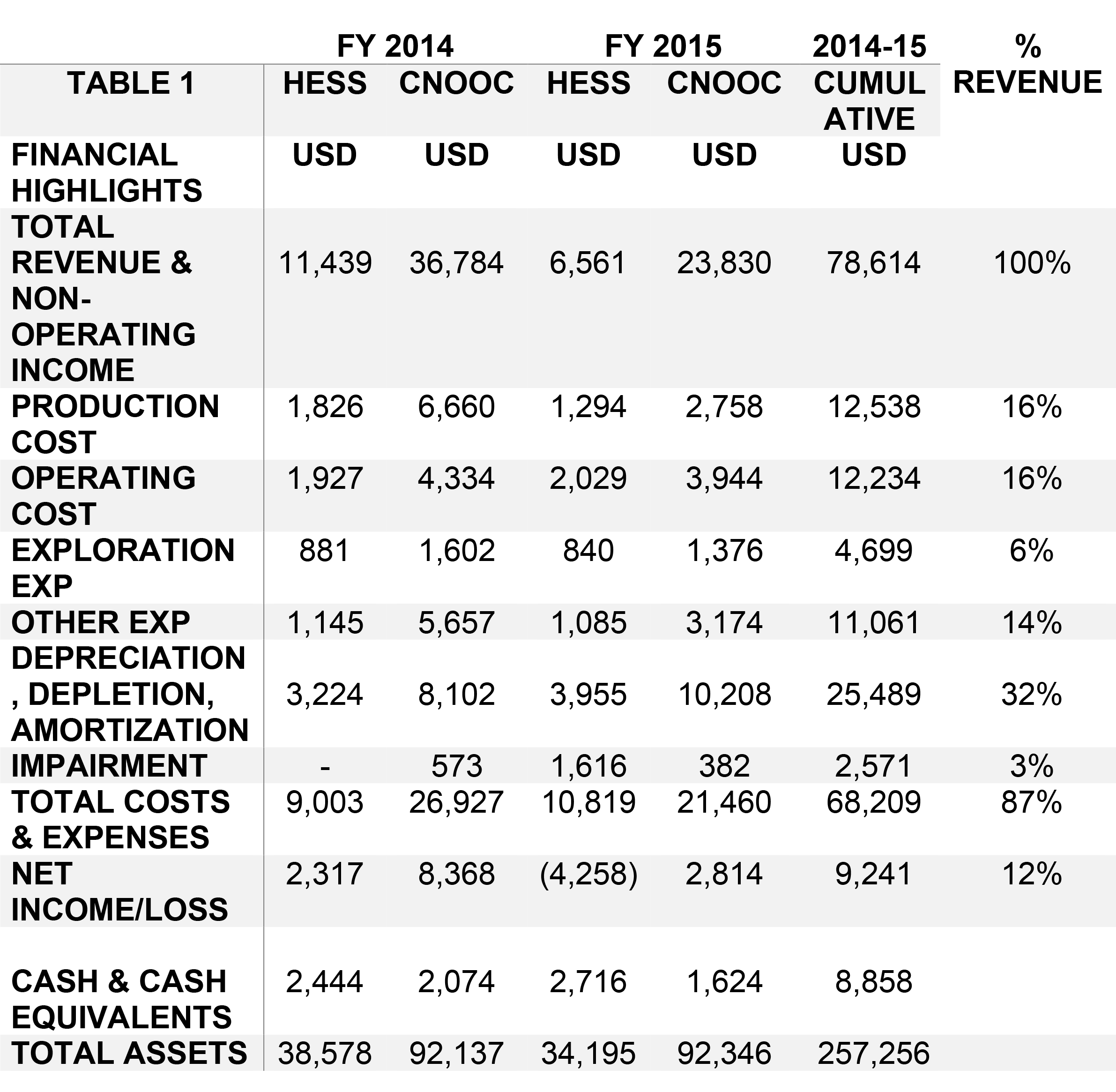

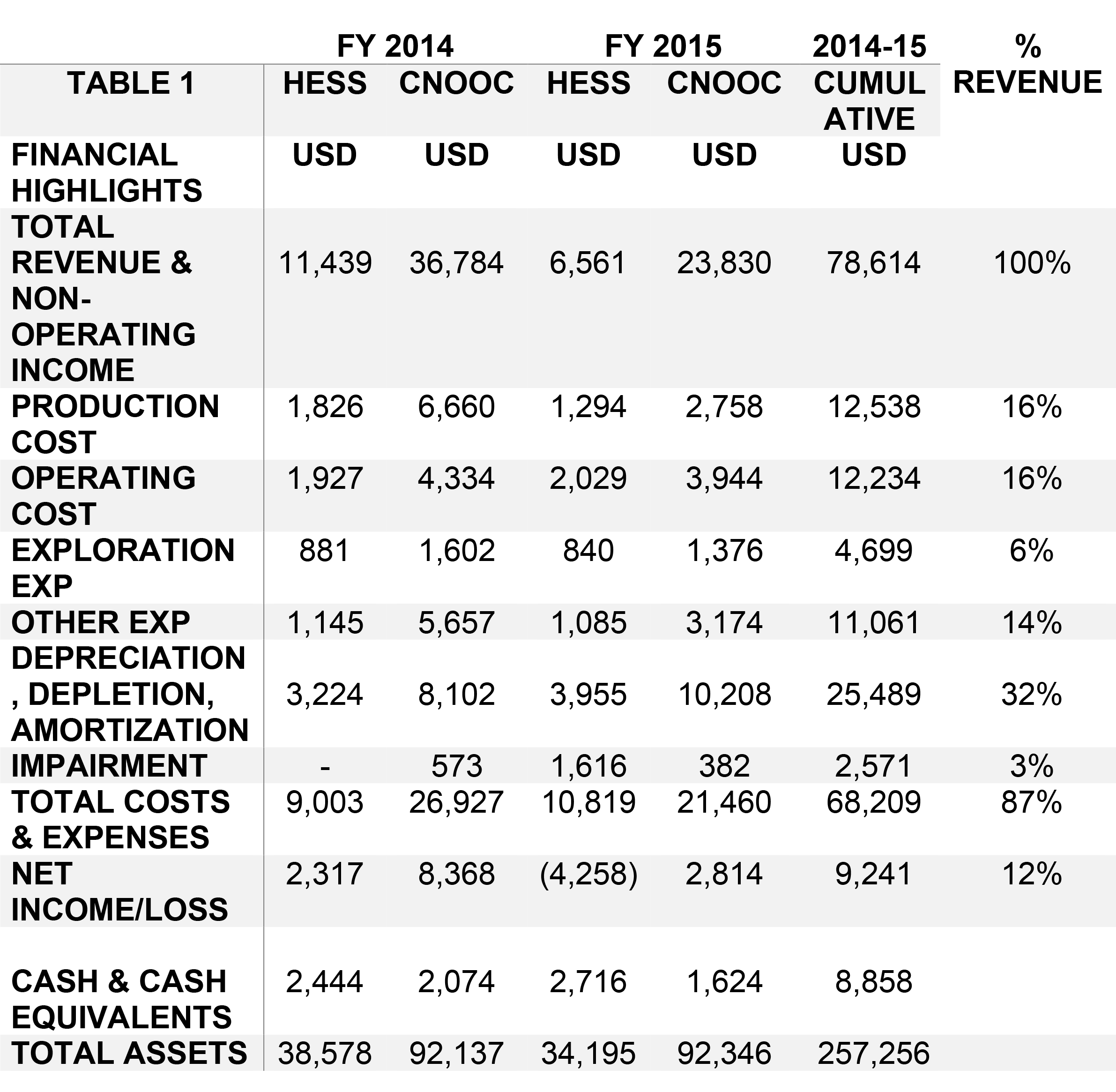

The financial highlights in the above table for both HESS and CNOOC were extracted from their annual reports for the years 2014-2015. For simplicity, let’s look at the cumulative figures of both companies for both years. Because, if there was any such transaction, it would have been paid over to ExxonMobil during this time. The cumulative revenue for both companies was US$78.6 billion with a net profit of US$9.2 billion. Notably, HESS made a loss in 2015 of US$4.258 billion.

The cash and cash equivalents for that period amounted to US$8.58 billion. Clearly, both companies could have never afforded such large sum of US$10 billion since the cumulative profit for both companies was less than US$10 billion.

Even if the political activist wants to argue that it’s hidden in the costs, this too, can be dissected and disproved. The production and operating costs alone amounted to 32% of the cumulative revenue. A transaction of this nature and of this size would not form part of the production and operating costs. If true, it could only come under other expense or exploration costs. And as a CPA holder, which I don’t have, Charles Sugrim of all persons would know this better than I do.

So, the exploration costs cumulative for 2014-2015 for both companies amounted to US$4.699 billion, not even half of the US$10 billion. Other expense which included items such as general and administrative expenses amounted to US$11 billion. Again, US$10 billion represents 91% of that cost. Therefore, to imply that the cost of such a deal would account for 91% of other expenses for these two companies is an unfathomably absurd notion.

Cognizant of the fact that Mr. Sugrim is one of the most highly qualified finance professionals, he can construct another argument. To this end, he can argue that because of the size of the transaction, it would not be reflected on the profit and loss statement. Instead, it can be treated as a capitalized expenditure which would be reflected on the companies’ balance sheet. Hence, there should be an upward movement in the total assets of both companies by at least US$5 billion, but evidently this was not the case.

In the case of HESS, total assets actually contracted in 2015 from their 2014 position of US$38.5 billion down to US$34.2 billion. And in the case of CNOOC, total assets increased from US$91.137 billion to US$92.346 billion, reflecting a marginal increase of 1.33% or US$1.2 billion.

Editor, the truth is that ExxonMobil, through its local subsidiary, Esso Exploration and Production Guyana Ltd (EEPGL), holds a 45% equity stake in the Stabroek block, Hess holds 30% and CNOOC holds the remaining 25%. These companies came together to form a consortium, and EEPGL is the licence holder and the operator. They all share the risks and contribute to the equity capital structure. Now that the Stabroek block is producing from Liza 1 and Liza 2, ongoing exploration and future developments are financed from the operating cash flow generated from these two fields.

Against this background, the argument advanced by the learned Charles Sugrim is void of logic, common sense, rational thinking, and reasoning. I say this because I have already proven above that HESS and CNOOC could not have afforded US$10 billion for such a deal. Considering this, if one were to look at ExxonMobil’s annual report for 2015, Exxon made US$32 billion in after-tax profit in 2014. This means that Exxon could have chosen to take on all of the risks, and today Exxon would have been enjoying 100% of the profit, as opposed to sharing 55% of that with HESS and CNOOC. With this in mind, it is worth noting that Exxon did not solicit partnerships with HESS and CNOOC because it did not have the financing to invest; rather, it is the nature of the risks associated with the industry. In so doing, it is a way of minimizing the risks by risk sharing through these types of arrangement. Of course, once there are successful commercial finds, they all reap the profits as the reward for the risks and return for their investment.

Finally, does Charles Sugrim really think that he can brainwash Guyanese by propagating this sort of unfounded and illogical narrative to captivate Guyanese for political gains? Can the people trust the likes of Charles et.al, that they actually have what it takes to govern a country, if their philosophy at the outset is to sell lofty dreams and transmit impractical promises?

Yours respectfully,

Joel Bhagwandin

Discover more from Guyana Times

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.