Home Features EPA Column Islamic financing and economic development: Third World developing economies like Guyana

In last week’s column, it was contended that the Islamic Financing Model would be more prudent to adopt for the financing of the new Demerara Harbour bridge project. As was indicated therein, today’s article seeks to provide an in-depth discussion on how Islamic

financing works and the distinguishing features of this type of loan financing–compared to the conventional development financing.

In the second half of the 20th century, when the Muslim world was liberated from colonial power, widespread resurgence of Islamic ideology took its path in Muslim societies. This led to the masses examining the existing social systems through Islamic lenses and proposed modifications and developments. In doing so, the Muslim thinkers and philosophers challenged the world’s ruling economic and social systems and uncovered their weaknesses (Hanif, 2011).

Three principles that govern Islamic

finance (Hussain et.al, 2015).

1. Principle of equity: Scholars generally invoke this principle as the rationale for the prohibition of predetermined payments, with a view of protecting the weaker contracting party in a financial transaction. The principle of equity is also the basis for prohibiting excessive uncertainty as manifested by contract ambiguity or elusiveness of payoff. Transacting parties thus have a moral responsibility of disclosing information before engaging in a contract, thereby reducing information asymmetry.

2. Principle of participation: although commonly known as interest-free financing, this does not imply that capital is not to be rewarded. According to Islamic principles, reward–that is, profit – comes with risk taking. Investment returns have to be earned in tandem with risk-taking and not the mere passage of time. Hence, return on capital is legitimised by risk-taking and determined ex post based on asset performance or project productivity, thereby ensuring link between financing activities and real activities. The principle of participation lies at the heart of Islamic finance, ensuring that increases in wealth accrue from productive activities.

3. Principle of ownership: The rulings of “do not sell what you do not own” and “you cannot be dispossessed of a property except on the basis of right” mandate asset ownership before transacting. Islamic finance, has thus come to be known as asset-based financing, forging a robust link between finance and the real economy. It also requires preservation of respect for property rights, as well as upholding contractual obligations by underscoring the sanctity of contracts.

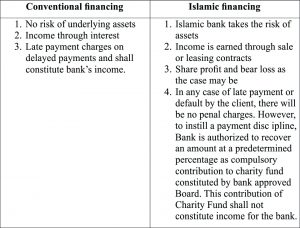

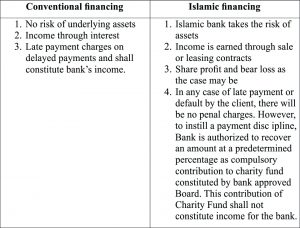

Differences between Islamic and conventional financing

The key principles that govern Islamic finance as outlined above, imply that in an Islamic financial system, financing can only be extended to productive activities, trade and real estates–thus it is often considered an asset-based financial system. If fully complied with, these principles ensure appropriate leverage and help limit speculation and moral hazard. Consistent with these key principles, there are two sets of Islamic models of financing, excluding fee-based services: (a) profit-and-loss-sharing (PLS) models of financing and (b) non-PLS contracts. A strong preference is attached to the risk sharing modes of financing, as they are closest to the spirit of Islamic financing. Additionally, even in the debt-like modalities, financing is linked to real assets, thereby limiting the extent of leverage associated with financing (Hussain et.al, 2015).

Conclusion

Having outlined the distinguishing features of Islamic financing compared to conventional financing– thereby establishing a basic understanding of how Islamic financing works; one may agree now that the US$900 million line of credit facility approved by the Islamic Development Bank is actually not a bad thing–but rather good for Guyana’s development. In other words, Islamic financing, technically, shall not push up the debt-to-GDP ratio, thus contributing to fiscal constraints to service such a type of financing as compared to the conventional development financing whereby such loans are usually serviced from the fiscal revenues of the Government.

Therefore, the Government has a responsibility to carefully select the appropriate productive projects– that will allow for the profit and loss sharing model for which the Islamic facility can be used for. In this regard, the new Demerara Bridge is a perfect example of a project for such. Other such suggestion can be the revisiting of the hydropower project, and setting up a modular oil refinery among others of this nature, and perhaps explore this option for the GuySuCo restructuring programme rather than the massive $30 billion bond, which, as was established in previous writings is devoid of financial prudence.