By Lakhram Bhagirat

Our culture, heritage, and practices are what distinguishes us from everyone else. In today’s world, we are rapidly losing all that we hold near and dear to us. Traditional practices that defined us as a people are being lost because of the need to integrate into a global culture.

However, not all hope is lost. Some people are determined to preserve the uniqueness that is theirs and make it their mission to educate as much as possible.

Never had he thought that the preservation of his culture and traditional practices would have been so threatened that he needed to step up to protect it. Now he is on a mission to ensure that the uniqueness of the Indigenous Peoples is understood and their practices remain.

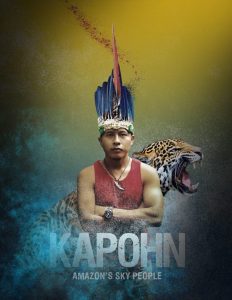

He calls himself Kapohn because of his Indigenous pride but the legal system knows him as Romario Hastings, a 24-year-old from Kako Village in Region Seven (Cuyuni-Mazaruni).

Kapohn or Kapong is an endonym of the Akawaio peoples. It means “sky people” (kak=sky) which speaks to the perceived closeness of the Indigenous nation with the sun – a source of life, as they dwell in the Pakaraima Highlands. As with most, if not all, of the Indigenous nations, the names they are known by today (whether Akawaio or Arawak) are merely corrupted versions of names attributed to them by their sister nation(s) with whom interactions occurred in pre-Columbian Guiana.

“Importantly, Kapong is a collective and an individual identity which determines relations with each other through language, customs, beliefs etc. Hence, by virtue of heritage, I am Kapong and my family is Kapong,” he said.

To understand Romario’s drive for preserving his heritage, one would have to first understand where he came from and how his experiences shaped him into the person he is today.

For him, his childhood in Kako was ideal. There were no gadgets, intrusion of addictive technologies, and everything was done outdoors in nature. Afternoons at the riverside were his favourite and included swimming with his cousins, playing “aquatic ketcha” and war-break with mud.

“Upriver expeditions for fishing and camping were hallmarks of my childhood, which contributed significantly to my appreciation and advocacy for the environment. I remember slipping in the rapids and broke my thumb. Education-wise, the challenge was the state of the under-resourced schools. For instance, our libraries were and are still outdated. I was also separated from my parents as they worked in a distant village for about 5 years but I coped fairly well with my grandparents. My greatest triumph was to secure entry into a secondary school on the coastland. Generally, it’s an experience for the books.”

As with the majority of hinterland youths, Romario’s nursery and primary education were completed in his community. He attended Kako Nursery and Primary Schools. In 2006, he wrote the Common Entrance Exam and was awarded a Hinterland Scholarship and was placed at President’s College. Subsequently, he enrolled at the University of the Southern Caribbean to study Theology in 2012. However, in 2014, he transferred to the University of Guyana and read for his Bachelors in Environmental Studies at the Faculty of Earth and Environmental Sciences. It was here, through research, that his interest in Indigenous peoples was born.

Kako is a small village on the left bank of the Kako River, named after a Jasper rock. It is a conservative community as Adventism is the predominant faith.

“We do have basic health services, school, and energy supply is limited to household generators and solar for some units. This is a key challenge which the community needs to address. Hopefully, with the green state framework, we can establish a solar farm soon. Kako has the potential for citrus production and processing and energy is of essence for projects like these.

Another major challenge I’d like to highlight for Kako relates to mining in the river. Tributaries of Cuyuni-Mazaruni are devastated by mining effluent and mercury. Our river, in the sense of stewardship and traditional occupation and use, remains devoid of such activities and we have dared to deter several miners by forestalling their equipment as a desperate effort to protect the river. We have faced litigation where cases were adjudged in their favour. But Kako remains steadfast in their position. Freshwater is shrinking at a global scale, and our river must remain within that meagre per cent.”

Coming from the Akawaio nation meant that there are some distinguishing traits from the other Amerindian tribes but to pinpoint this is somewhat difficult for Romario since he has not lived among the other nations. However, off the bat, he identified the practice of the Alleluia religion, which is a syncretic religious system of Christian and Indigenous beliefs.

“We have the parishara and tuguit dances. Casiree and Piwari making is also prevalent as opposed to fly and parakari. There is also a special naming system for our different river groups unlike the Savannah Indigenous groups such as Kuguigok vs Kakologok. We customarily sequence our livelihood activities based on our ecological calendar which is peculiar to our geographic area. In fact, we now approach the Wei pia season in Upper Mazaruni.”

Romario is fluent in Kapong maimu, meaning the Kapong language which binds together his people as one. He now feels it is his responsibility to transfer this language to future generations.

When it comes to protecting the very culture that makes his people unique, Romario said:

“I think we have a long road ahead in protecting our culture and I believe this begins with the collective vision and demands of the people themselves. Our family units, livelihood practices and our ancestral territories form the nucleus of our culture. The magnitude of our cultural loss is immeasurable and continues to decline. But one will only understand such loss if one knows what existed, which is the sad situation of many Indigenous youths because Indigenous history is not commonly taught exhaustively.

“The integrity of our rivers are starkly diminished. We continue to struggle for rights to our ancestral lands. The education system is not wholly integrative of our worldviews, realities and knowledge systems especially when schools have replaced our cultural learning institutions and methods of learning. Our languages are sometimes discouraged in an attempt to erase social stigmatisation at a household level, among other issues.

In essence, protection of our Indigenous culture spans a myriad of fundamental issues which remains to be addressed from the grassroots to policy levels. But as Kapong people or Indigenous peoples, we must want and assert this cultural continuity, and our youths must propel this movement as we become empowered.

“I think relearning and embracing your cultural heritage is in itself an act of cultural reawakening which through sharing and the intergenerational transfer will translate to preservation. We must accept who we are first and foremost before speaking about preservation or protection. Preservation will not manifest through exercising indifference, conscious aversion and outright neglect. It’s easier for Indigenous youths to shun their culture than to revalorise it which stems from decades of cultural dissent and ridicule from the dominant society. It’s okay to eat cassava bread or Tacoma. It’s okay to speak your language. It’s okay to express your roots. It’s okay to relearn what was lost. It’s okay to be different. Change the narrative and own your identity and let us experience our own cultural revolution and evolution.”

Romario is currently an Environmental Protection Officer with the Environmental Protection Agency but foremost, he is a teacher. A teacher in the sense of educating those about his culture and practices. He takes his role as a teacher with pride as he shares his journey of relearning and imparting.

“My academic career and community development constitute the core of my long term goal. I envision Kako being a model community and hope to work in a closer relationship with my people and embark on projects that fulfil our social, economic, environmental and cultural aspirations. And I do aspire to be a phenomenal Kapong Akawaio Chief.”